Rx

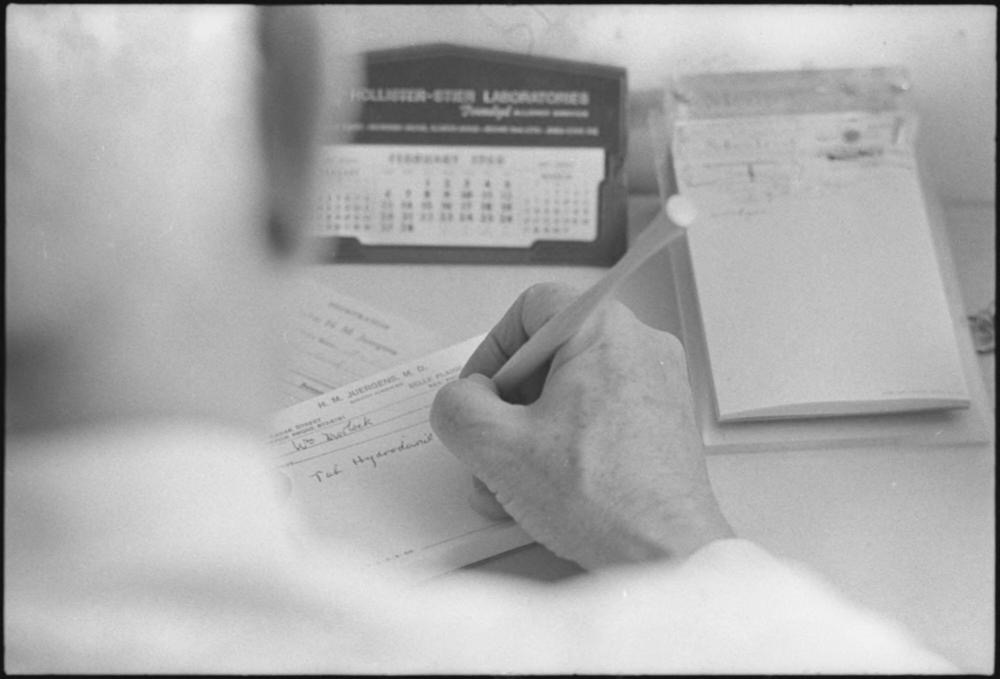

Gordon W. Gahan:

Untitled [Dr. Herman M. Juergens writing prescription] (1965-1968)

"Imagine how fortunate I feel to have been able to barter for a few of those…"

When Roading, the most memorable experiences arise not from planned activities but from inadvertencies: a wrong turn onto a road never intended to be taken, a whim, an obvious mistake. These are the fuel from which the most epic stories emerge and the greatest lessons are taken. If one believes in predestination, it might be easier to insist that some wiser hand guides these, that somebody 'out there' was deliberately teaching you precisely the lesson you most needed exposure to, but these seem more likely random occurrences, with meanings self-imposed, however otherwise profound and unlikely they might seem.

A single degree change in intended trajectory results in a dramatically different destination. I suspect that this discloses the true attraction to traveling. We might only plan in considerable detail to distract us from the fact that those plans, however detailed, could never happen as imagined. That planning serves as part of the setup for what inevitably becomes another practical joke, bringing more impact than any planning could ever induce. It's sometimes possible to talk oneself out of these detours. In the moment of inspiration, any old wild-ass diversion might seem overwhelmingly attractive, though a little more sober reflection might convince anyone to avoid roads that really should never be taken. What initially appears to be a revelation becomes little more than seduction, with consequent reparations owed. A moment of consideration can and has stemmed some abysmal decisions.

I left my toiletries bag at The Muse's brother's place as we passed through on this excursion. I realized what had happened about a hundred miles down the road. In even the minor scheme of things, this event hardly seemed consequential, for we had planned on returning to the scene of this minor crime in a scant two days' time. I would be reunited with my prescriptions just a couple of evenings later, so I could probably just get a two-day supply from a pharmacy near The Muse's oldest sister's place. I phoned my home pharmacy to confirm what I already knew: they'd have to transfer every prescription to the interim pharmacy to fulfill my request. Oh, and the insurance company might not allow a refill so soon after the prior refills, this, I suppose, to avoid liability and fraud. I was reminded that drug companies are not necessarily in business for the convenience of the patients dependent upon their benevolence. They more often fulfill the role of potentially vengeful god than lord or savior. One carefully tiptoes around such despots, and emergency two-day refills tend to put the requester on a radar nobody ever wants to be registered on.

The clerk warned me that the refills might not be ready immediately, but that she would let me know when they were ready by text message, which is probably the best way to ensure that somebody my age misses the notice. I try to remember to check my texts every few days, but they're not near the top of my usual priorities, and I've not been able to determine how to get them to notify me when they arrive, so they amount to a random means of notifying me, and I suspect, most everybody. Still, the convenience for the sender probably more than outweighs the inconvenience the intended receiver experiences, so in today's odd commercial calculus, texting tends to be how providers inform their customers.

I tried to pay attention and found a text notice from them only three hours after they'd sent it the following morning. By then, I'd already missed the prior evening's course of medication, except for the one pill my sister-in-law's husband offered. He had been prescribed the same drug and had a few extras, so we decided to trade. I'll pay him back when we reconvene at a family event over the upcoming weekend. The text notice reported that the refills had been delayed because they were out of stock. It didn't occur to me that the attached message might include more information, but when, a couple of hours later, I found that it had, I learned that five of the prescriptions had been refilled. I headed out for the pharmacy to collect my reward.

The prices quoted for the two or four pills requested matched what I'd grown used to paying for a thirty-day supply of each. Except for that one prescription, for which I had been bartering, which was quoted at $55 for four pills. I usually pay $35 for thirty of those, but, I suppose, usury insisted that they charge a premium. I didn't accept delivery of those because, frankly, I'd rather pitch an embolism than pay that king's ransom extortion for that medication. The others, the clerk was able to reduce the price slightly using a combination of supplemental insurance queries and GoodRx. I left only twenty dollars lighter than when I arrived, and felt grateful they hadn't sent me away wearing a barrel, which they could have, and had even tried to accomplish.

I told the clerk to cancel the sixth prescription, the one they'd back-ordered. I told her I would likely be gone by the time it arrived, but she insisted that I stick to the plan. I won't be back to collect that one. Then, at the end of the month, I will request that the six prescriptions be transferred to my regular pharmacy for refilling back home. The insurance company, ever-vigilant, will likely question the legitimacy of my request, since I'd just refilled it a couple of weeks previously. That they hadn't anticipated this fairly predictable situation astounds me. People prescribed these medications tend to behave like Mr. Magoo. We are predictably forgetful to a fault. We can be relied upon to behave predictably unpredictably. A procedure to deal with misplaced prescriptions hardly seems like it would be covering anything even remotely resembling a rare exception.

I will survive this insult. I'm almost accustomed to the inconveniences that our much-vaunted healthcare system involves. I'm accustomed to the impenetrable patient portals and the routine inconveniences record capturing and keeping entails. I'm grateful that my internist, at least, presents as human. I reward him by scrupulously following his directions, actions he considers nearly unprecedented. I'm healthier as a result, hopefully healthy enough to survive some disruption in the otherwise smooth administration of my several prescriptions. I'd rather not pitch an embolism than pay through the nose for the privilege of avoiding that fate. The pharmacy clerk remarked that the gold-plated drug without insurance costs a thousand bucks a month, and the fifty-five-dollar price for those four pills represented a considerable discount over the full retail price. Imagine how fortunate I feel to have been able to barter for a few of those with The Muse's brother-in-law.

©2025 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved