FairToMiddling

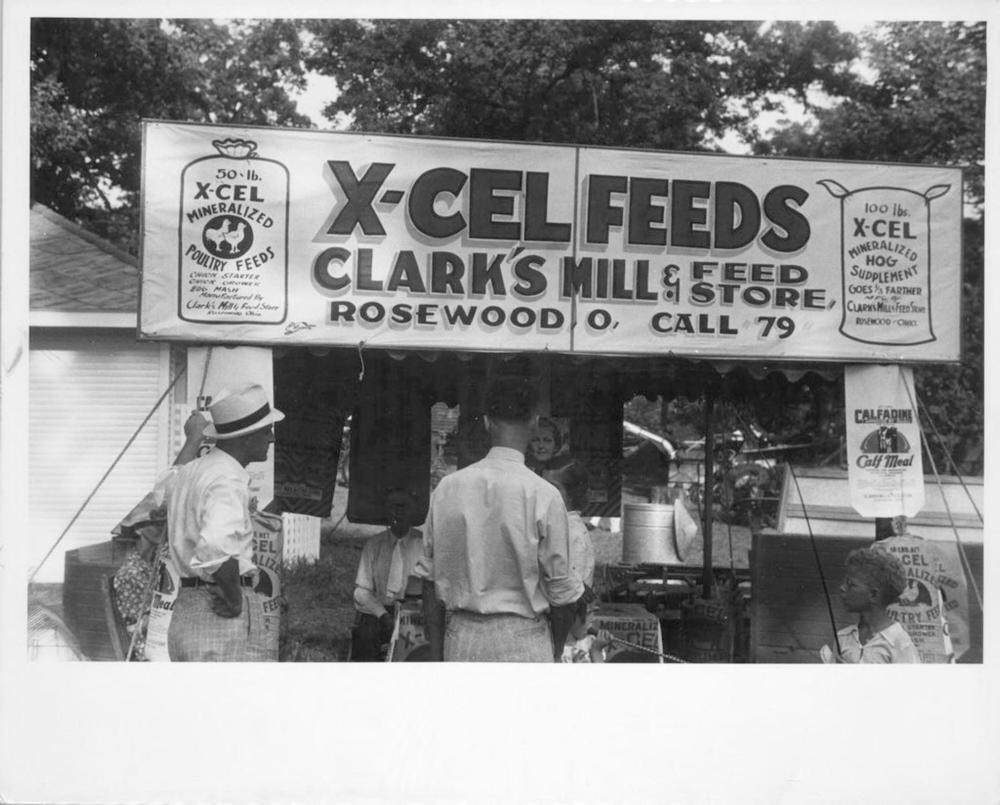

Ben Shahn: Untitled [county fair, central Ohio] (August 1938)

"…some vestigal and rarely-recognized part of me."

Few institutions better typify rural American civilization than the county fair. It was there when my grandfather was a youth, and it has somehow survived well into this post-truth era, though not in any way intact. In my youth, it was an absolutely must-attend affair, one for which schools closed two days after opening so students could attend the opening on Friday, so-called Kids' Day. The farm kids entered competitions to see who'd raised the handsomest chickens, and we townies would attend with friends to haunt the midway and vomit our obligatory corn dog when riding the Tilt-A-Whirl. Later, we'd meet up with a girl and squire her around the place as if we owned it, which, in some ways, we did. I'd wear a paper Rossilini for Governor visor and feel every bit the fully-fledged responsible citizen.

When The Muse was coming up, she entered sewing projects in her fair and garnered purple ribbons, signifying the best. She even earned a place at the State Fair one year. Her mother was an enthusiastic Girl Scout leader and sponsored many future farm wives in their first few crafting ventures. It sparked considerable enthusiasm when she discovered that the Brown County Fair would be happening during our visit. I knew for sure we would be going.

County fairs might well be universal across rural America, but in my experience, no two are very similar. Some seem more rodeo-heavy while others focus more attention on agriculture. Some seem little more than farm equipment sales events, while others focus more on concerts. Up-and-coming as well as downward spiraling acts book almost exclusively in fair circuits. For July and August bring more than enough Fairs to fill out a traveling schedule. The Brown County Fair didn't seem to involve any rodeo, which seemed understandable, since Brown County sits East River in South Dakota. East River features farms, while West River features ranches. Cowboys were never very similar to farmers. Unlike the local fair at home, parking was free in lightly flooded and swampy lots around the fair's perimeter, and there was no admission fee; the whole shebang came free of charge.

We bee-lined for the midway food carts to find the usual collection of offerings: five different shapes of fries —curly, ribbon, fresh-cut, krinkle, and tot. Corn dogs, including ones with bratwurst inside. The obligatory cotton candy, which doesn't quite qualify as food to me, and a spattering of ethnic food, including Greek and Italian. Lemonaide was offered in sizes up to and including a refillable half gallon, complete with a lanyard string, and ice cream in various guises, including one labeled "Ribbon." I chose a Greekish Gero sandwich as we ambled toward a barn labeled "Home Arts," hoping to find a display of handmade quilts inside.

The stumble commenced there, the ambling semi-stroll intended to transport one from here to there at a fair. It's a stilted walk, one that never quite achieves anything resembling a stride. We stumble through the quilts, stopping frequently to comment on colors and styles while I munch my sandwich, using a fork to nudge its pieces apart. The Muse's brother catches up with two kids in tow, so we head off to another barn, this one displaying more commercial concerns. Everything from funny little air conditioners to political candidates are on display in there. One of The Muse's nephews wins a barbecue spatula at the T-Mobile booth.

I ask a candidate for Lieutenant Governor if she's a Democrat and get a sour face in response. I notice her campaign slogan includes "Faith" as part of her platform, so I ask her stance on the separation of church and state. She claims to be opposed to it. I point out that the concept is enshrined in our constitution, but she denies it. She claims it's more rumor than practice, mentioned in a letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Adams. I brought up a handy copy of our constitution on my phone to show her the First Amendment, which forbids the establishment of a state religion, and she was incredulous. She didn't believe it and couldn't accept that her government might forbid what she was promoting with her candidacy. We moved on past yet another anti-abortion "pro-life" booth featuring far too graphic images.

We eventually found ourselves in a barn where a sow was on display, giving birth to piglets. A large crowd "crowded" around to watch the blesséd events. I found this a tad too Circus Maximus for my tastes, so I sat on an all-too-rare bench to rest my back while the kids watched the pigs before going on to play with baby chickens. I wondered about the wisdom of allowing children to play with baby chickens while bird flu remains unconquered, and decided I might be overthinking my experience. The problem with trying to organize and execute a fair after enlightenment might be that too many questions remain unanswered to justify the innumerable risks involved. Fairs provide the perfect medium within which any virus might spread faster than wildfire, yet they also provide something essential for survival.

On our way out, we stopped by the obligatory Centennial Village, a corner of every fairgrounds reserved for paying homage to the county's founders. There, displays of dust and mildew evoke memories of the good old days. That's also one of the few corners where they allow beer to be served. That corner proved popular as the humid afternoon was threatening to stretch into evening. We limped back to the car, feeling better for the experience, but tired. We'd been to the fair, a designation that once elicited visions of a kind of enlightenment available to even so-called ordinary people. Fairs provide the experience of still living in a society that mingles, even though we mostly mingle online today. They give the kids a few concerts and opportunities to stroll through barns arm in arm, as if purposeful. They're mostly an exercise in nostalgia, and relatively harmless.

In two weeks, we'll be home and attending our own fair and rodeo, the one by which we judge every other fair we might attend. I did not end up ordering any deep-fried Twinkies or candy bars, and I just stuck with that one sandwich, though I couldn't stomach the bread that came with it. I recognized that I had participated, mainly as an observer, in one of the great American myths, and I dutifully appreciated the experience. No, it didn't change my life in any meaningful way. I did not fold to the barker who tried to improve The Muse's face with futuristic collagen treatments. I strolled and stumbled, and felt humbled by the presence of so much variety before me. Where else would I encounter a sow giving birth to piglets while families rubbernecked around the spectacle? Without these experiences, I might be tempted to think of myself as somehow apart from humanity, rather than inexorably embedded within it. Even a deep-fried Twinkie probably mirrors some vestigial and rarely-recognized part of me.

©2025 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved