ParadoxCountry

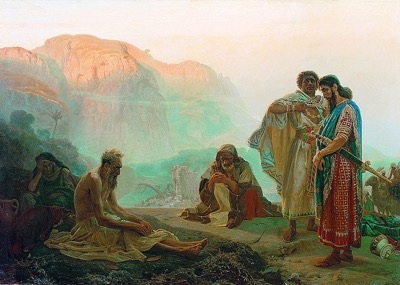

Job and His Friends, 1869, Ilya Repin (1844–1930)

"I suspect that it will always be too early to tell what the outcome might become."

Winter eventually becomes too predictable, with each day bringing a wearying self-sameness. The yard remains either a steadfast beige or a persistent white, and the kitchen produces endless braises and bean pots. There are only so many variations, and those differences eventually melt into no variation at all. Foot-dragging ensues. Whatever's doing, it seems a struggle to start and an utter impossibility to complete. Frozen in place, little change or growth or improvement seems likely to emerge. Animation seems to suspend for the duration, and the duration approaches the infinite, for the more familiar spring, summer, and autumn reference points sit beneath a snowbank likely to remain in place until after Memorial Day. Getting away seems necessary, though unlikely. The Muse insists. Who would anyone have to become to effectively resist her?

From the moment The Muse, The Otter, and I pull away from our freshly snow-spackled driveway, we feel more at home. The Interstate, a terrifyingly threatening barricade less than a day before, seems a possible route toward salvation by then. I surreptitiously carry my existential dread of The Eisenhower and Vail Pass, and I continue forward, grateful that nobody save the odd BIG-ass Dually seems destined for Perdition. We somehow survive the slushy passes, keeping our asses tucked in between semi-truckers who know better than to drive like Hell in that kind of weather. Once past Vail, the road turns bare and dry, though it takes me a few miles to open up the schooner to the full seventy-five speed limit. Glenwood Canyon floats by as if we were being transported on a slide. The Colorado Plateau likewise easily slips by and we're soon zipping through the Palisades and onto the edge of The Great American Desert, which seems almost paradise to our eyes after so many weeks of red beans and braising spices.

The Otter drives, a concession that only I, as the traditional driver on these toodles, must extend, though I can only remember the rambunctious eight year old she once was as I attempt complacency in the back seat. Nobody dies, though the straight, flat eighty-mile-per-hour road surface insistently bucks the car into behaving like a frisky colt, for nothing's actually flat in this land of expansive soils. Every paved surface holds waves which yield a certain chop. I learn as we approach Moab, our destination for the night, that we'll be staying on the edge of ParadoxCountry. Just over to the east of us lies a river valley originally inhabited by Utes, a "fierce" and "untamable" tribe known for their "chicanery." History characterizes them in terms that only a backsliding Christian could ever appreciate, as if THEY were the recalcitrant children, as if THEY needed taming. Squatters soon overran this corner of Ute Country. Our much-revered settler ancestors were often not intrepid adventurers but squatters, belligerently sitting before settling, often on land to which they had no legal claim. That land was re-christened Paradox County, Colorado. The government, our government, usually chose to wrong the natives' rights, ceding land they'd previously 'given' whenever some economic potential emerged. The paradox of the settling of The Land Of The Free: "braves" were usually barred from their own ancestral lands to create The Home Of The Brave.

Arches National Monument rises just north and east of Moab, a lovely-ish little place stretched along a still lazy Colorado River. We pass through a settlement called Potash as we approach the town, a railroad siding we later learn has become where the Department of Energy works to reclaim discarded uranium mine tailings. ParadoxCountry once held the richest deposits of radioactive ore in the world, until richer deposits were discovered in the Congo. The remnants of those riches now impoverish the place, ensuring that its visual riches will remain surrounded by radiation for the next few millennia or so. It was great while it lasted, though, with one road, The Moki Dugway, built in the late nineteen fifties as a route for transporting uranium ore to the now toxic mill outside Moab, leaving as heritage an impossible two miles of ten percent grades and switchbacks up and down the face of an enormous mesa.

Mesa is an overused word here, for mesas of every size abound in ParadoxCountry. So do piles of what appear to be petrified dinosaur poop and the remnants of ancient salt domes sculpted by wind into towering red spires with the occasional natural arch and apparently balancing rock. To stunning visual effect, Arches National Monument seems an authentic impossibility, actually awe-inspiring. La Sal, a curious little upthrust snow-capped mountain range frames the red rock visual effects. Those arches and spires began as prehistoric salt domes which time ultimately exposed. They're sandstone now, perhaps the least permanent mineral, but studded with deposits of the very most permanent minerals around. A far distant jet engine produces the only sound save the lightly luffing wind as we stand gape-mouthed on an unforgiving rock prominence peering at an arch silently arcing in the distance. Long shadows overtake our day spent escaping the dead of winter. La Sal turns pink then crimson in the further near distance. When darkness comes, it comes absolutely, leaving the heavens filled with suddenly not so distant stars.

We'd come farther than the three hundred and thirty-some miles the odometer clocked. We'd traveled from familiar obscurity into deep paradox, the sort of advancement one might reasonably expect from any winter determined to retain its bonds. The absence of wind struck me as at least as noteworthy as all the stunning visuals, for this country was carved by incessant wind and I don't know where to begin to explain why it abandoned us once we arrived here. The national park features seemingly endless biblical-inspired place names—devil's this and angel's that—as if our squatting forebears were pious and the land they conspired to swipe was equally blessed and cursed. The worst that could happen, happened to the Ute, yet they've survived, casinos thriving on the squatters' great great grandchildren's tenacious innumeracy. The best that could have happened, happened to the squatters, who thrived as expected for a generation or two before inheriting the abject fruits of their successes. Our hotel holds a sign in the elevator lobby imploring guests to Help Save Art In Schools, and to make contributions at the front desk. The Muse mumbles, "Save your own damned art in schools. Tax yourselves!" She goes on to complain about how everything's become Pay To Play, life degraded into endless Kickstarter® campaigns, when we might choose self reliance instead. We're still squatters, I suspect. We stole this great land fair and square, so why should our modern times prove any less crooked? We might eventually grow to accept that our only escape might come from exiting the same/old and entering into ParadoxCountry for a spell. I suspect that it will always be too early to tell what the outcome might become.

©2020 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved