Clatterglories

"I wonder if it might be possible to categorize books by their ability to cast that spell."

Have you noticed how category-oriented we've become? I wonder if we were always this way. The corner store down the street from where I grew up seemed a jumble. Other than the butcher's shop in the back, the place seemed to have avoided departmentalization, and could seem chaotic to the inexperienced shopper. Over time, everything just seemed to be where it belonged, which perfectly correlated with where it had always been. A typical pantry isn't organized anything like a modern supermarket, with package shape perhaps more strongly influencing where an item gets shelved than any proximate similarity of content. I enter a BIG box store and spend most of my visit trying to figure out the central organizing principle, often coming up empty-handed and fleeing rather than asking for help. Asking an employee at The Home Despot where to find a particular item might or might not improve your chances of locating that item, for their classification schema seems a mystery to everyone, shoppers and clerks alike. ©2019 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

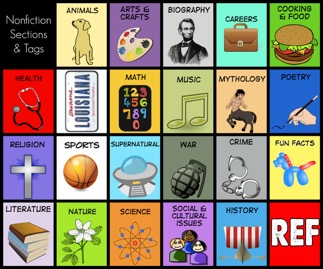

I shouldn't have been that surprised when my wise advisor confided that the first step of publishing a book involves properly classifying it. He asks if it's fiction or non-fiction, a slippery question for a writer like me. It's not exactly fiction since it exhibits little in the way of made-up characters or plots. Likewise, it's also not the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, guilty of certain embellishments and hyperboles common to fictional works. It's overall more true to life than imagination, so I suppose I could begrudgingly accept a non-fiction classification. Within that broader, rather imperfect box, then, what genre best describes it? Young Adult? Mystery? Food? Anthropology? Philosophy? Attempted classification quickly clouds the conversation.

What other works seem similar to this one? If I were more broadly read, I might be capable of responding. I suppose it's every author's conceit to believe that their work is the first work ever created that fully qualifies as non-derivative, that is, not crafted under the inspiration of any previously published work. I also suppose that it's another part of every author's conceit to find unreadable any book remotely comprable, thereby sealing their sense of utter uniqueness. Perhaps this work will spawn a wholly new category, one previously undeclared for lack of a single exemplar. Maybe, but probably not. I leave this conversation with the imperative that I must find some way to classify my work, a subtle double bind if ever I'd been tangled up in one.

Then I remembered a friend who teaches library science at a prestigious university. Maybe I could invite him to classify this work for me. I ask and he quickly agrees. I will, of course, retain the insulant right to reject his conclusion, but I'll probably choose to not exercise that right. I feel enormously relieved and a little disturbed. I'm questioning categories now. The Library of Congress maintains unarguably the finest book classification system ever devised. They also maintain the largest book collection ever assembled in the history of the world, so it follows that they've devised the finest central organizing principle. One quite literally needs the assistance of a librarian to navigate using it. Your municipal library employs a much simpler system, one depending upon broader categories, perhaps better suited to their much smaller collection. In the Library of Congress, locating the target classification is key. Identify a specific index number and the user will gain access to everything: fiction, non-fiction, fantasy, young adult fiction, mystery, … relating to that subject. In the municipal library, you'll have to scan the stacks and hope for the best.

I imagine some HUGE box store of the future requiring every shopper to classify themselves as a precondition for entering the store. Some will be able to quickly explain their presence there. Others, real shoppers for instance, might hold little more than a vague notion of where they want to go and what they might purchase. They'll know it when they see it and come prepared to browse. For these folks, categories hold little attraction. They could care less whether the mastic gets displayed adjacent to the bathroom tile. For the contractor whose job is stalled needing supplies, ease of locating a specific item becomes paramount. For me, in the local library, I check to see what's new and what's set aside as possible treasured finds. I almost never creep through the stacks. I rely upon a tacit third level of categorization, synchronicity. If a book's on a stand atop the Staff Picks table or displayed along the Lucky Day wall, it might catch my attention. My curiosity might encourage me to pick it up. I might then borrow the damned thing without ever once checking to see what genre or category it was classified under, a primary attribute to publishers and librarians but not to authors and readers.

I asked the late Philip Kerr, author of the Berlin Noir series, how he determined what his readers wanted. He replied that he'd not spent a moment of his professional life thinking about that. His novels were classified as Detective Novels, though several of them hardly qualified as such. His range included history, romance, and at least another dozen sub-classifications. He's remembered as a masterful mystery writer, though his readers recall his extraordinary writing ability. He told stories well. Whether those stories were factual or fictional never mattered to this reader. That they could cast that curious spell mattered most. I wonder if it might be possible to categorize books by their ability to cast that spell.