ADoorInc

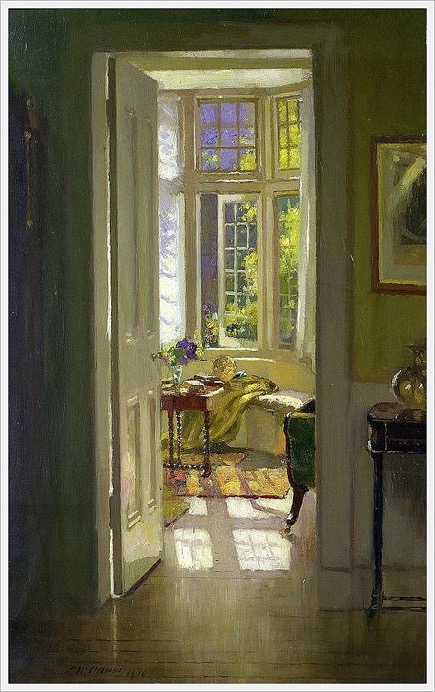

Patrick William Adam: Interior Morning (1918)

"I intend to paint in humble adoration, invisible masterpieces for the ages."

Like any old place, The Villa Vatta Schmaltz has a lot of doors, twenty, depending upon how I count them. A few must be original to the place for they're exercises in mortise and tenon joining, their heritage obvious by looking at their edges. Most seem of more modern heritage, but still solid five-panel doors, none of those hollow core abominations. Two appear irreparable. The rest need differing degrees of restoration ranging from simple painting to full strip, sand, prime, and finish. All need hardware stripped and probably replaced with brass. The painter visited yesterday and we roughly laid out the work before us. He approved our color palette and I took responsibility for the doors and two of the windows. I removed the first door last night, signaling the start of a significant side chapter in our overall restoration effort. I cleaned out the garage to make way for my door factory wherein I will refinish a dozen doors over the upcoming weeks. I'll erect a pop-up tent over a tarp, move in my saw horses and a work table, then tuck down my head and start refinishing. I'm calling this operation ADoorInc, though it's incorporated in spirit only and strictly not for profit, quite the opposite. It will certainly serve as a significant expense in terms of both money and aggravation, but I loves me doors. I imagine that I'm not merely refinishing them, but adoring them: ADoorInc. Get it? ©2021 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

I suspect that by the time I'm halfway through this pile of doors, I might no longer or ever again adore doors. I might permanently satiate my attraction to them and spend my days praying for deliverance. Once upon a time, this town had a millwork shop, an operation specifically set up to refinish and fabricate, but they closed. Now a bare amateur like me must buck up and accept responsibility for such things, though he wouldn't countenance any of the noisy and dangerous saws and such any half-decent millwork shop might possess. It's sander and scraper and chisel and plane; three coats of paint then on to the next one; juggling a queue with conflicting stages: stripping, chiseling, sanding, and planing seem like sworn enemies of painting. I begin this part of the adventure equally excited and daunted, wrestling with my dread of all I can't know yet and the clear understanding that I will be learning, which means I'll be especially prone to accidents. I must maintain a discipline most HomeMaking never demands. My work won't prove perfect, but will it seem good enough to seem invisible?

By long-standing international agreement, doors must be either dramatic or invisible. Dramatic doors might be painted a bright color or hold an unusual knocker. I once spent an enormously satisfying afternoon strolling around Florence taking pictures of dramatic doors. Plague doors, little tiny things set down and off to the side of a formal entrance and used for slipping out the bodies of plague victims, were surprisingly common. These were sometimes Minii-Me reproductions of the formal entrance, down to scaled wrought iron hinges and knocker. Other doors seemed just ancient, rough and cracked, constructed from perhaps thirteenth century oak. Nobody's about to refinish those babies. They're doors for the ages. People want their interior doors as invisible as possible, but invisibility's not easy. Like flat ceilings, which are likewise expected to float above without drawing attention to themselves, doors frame an entrance or exit, negative space into the more distant positive, and have little life for themselves. They must imply ease of access. Cracks or crappy paint jobs, even painted over hinges, suggest that there might be a failing barrier rather than open access, which induces distress. The knob must work and seem age-appropriate. The strike plate smooth and shiny. Hinge hardware bright. Above all, the panels must appear in sharp relief without obvious gouges, cracks, or sagging finishes. Hung right, nobody will notice their beauty. Done poorly, they're just about all anyone sees.

Doors are tough. Interior doors are made of the softest wood, easily gouged. Their softness means they can be deeply sanded, though, made to appear more whole and unviolated than most eventually become from regular use. It's all extremely delicate work, no bull-headed rough stuff allowed. A door demands light touches from a gentle hand. Inadvertent gouges serve as the door refinisher's greatest fear. A second of inattention buys an extra hour or two of recovery effort, if recovery's even possible. One must foster adoration for these babies. Success lies neither in speed nor forcefulness. Each door was once a masterpiece of design and construction and this heritage must be deeply respected. A hundred techniques might serve to fool the eye into believing that they're not seeing anything at all. My masterpieces will become invisible if I can muster the skill. I must remain mindful of this tacit purpose.

This damned heat wave complicates everything. The afternoon sun has been fully capable of blistering fresh paint, as it managed to do in a few places on my freshly-painted front porch. Dust is a demon that drifts in invisibly and seeps into crevices forever. Overnight dewfall, even when the relative humidity's in the teens, can speckle an otherwise perfect paint job. A cat jumping up to investigate leaves footprints not always easily erased. I should stop imagining failures or I might encourage their emergence. I guess I'm supposed to enter all innocent, as innocent as an invisible door might seem. I can remain cognizant without talking myself into corners. As usual, HomeMaking demands at least this much, that I enter with a quiet faith without much in the way of proof yet. As the sole proprietor of ADoorInc, I own my fate. A light heart seems essential. Optimism must reign. I should accept my ignorance for just what it is, pure potential, and not what it isn't yet and might never become. Our painter will serve as my wise adviser and he's an old and trusted friend. I met him when we were still in college. He painted my Portland house back in the eighties. He can tell me when I'm full of shit in ways that I can hear. I intend to paint in humble adoration, invisible masterpieces for the ages. What could possibly go wrong?