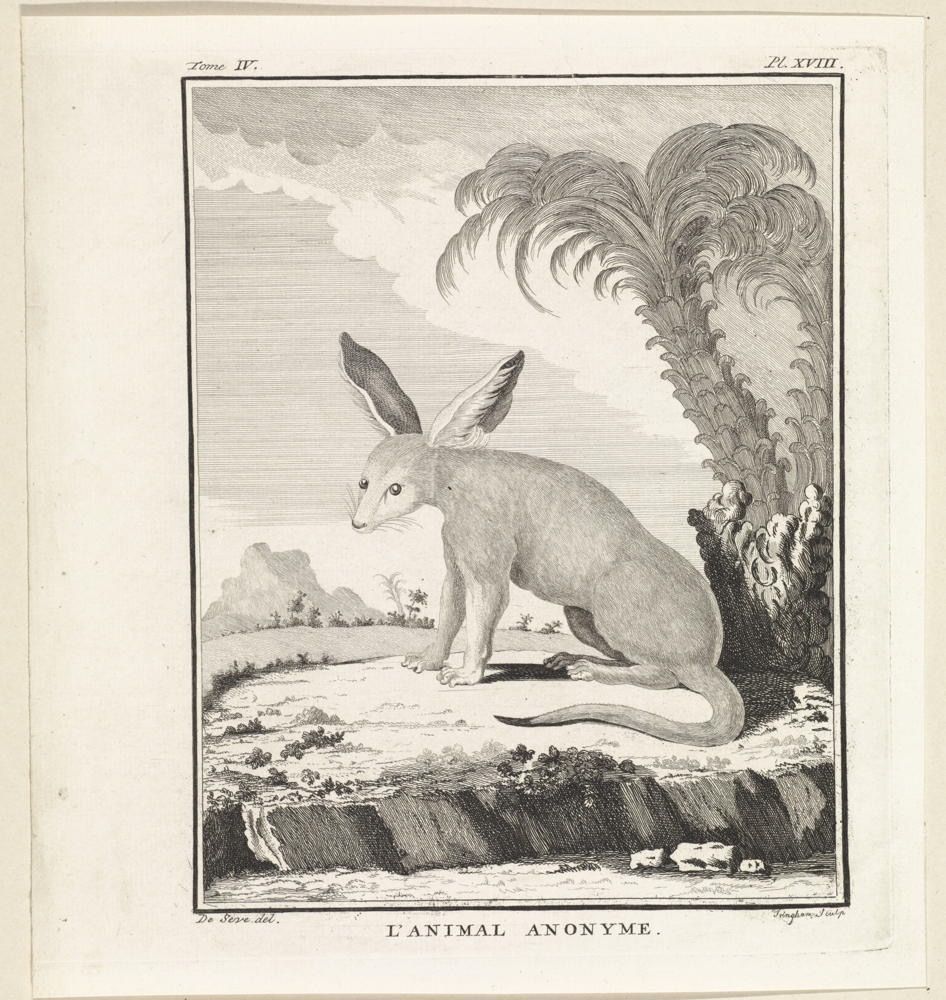

Anonymity

W. Tringham, after Jacques de Sève:

Onbekend dier [Anonymous Animal] (1773)

" … I sense myself a better man …"

Anonymity might be the one utterly reliable superpower that the newly Exiled possess. Though stripped of most of their possessions, they all acquire this one in exchange. It might initially seem freeing to move about the world with nobody watching or anyone watching having no clue what they're seeing, but this gift has indefinite limits. The anonymous hold little influence. They have nobody they can call to help them out should they get themselves into a jam. They can go anywhere without fear of being recognized, but they tend to roam few places where such recognition might matter. It's as if they exist without any observers, without any risk or hope of accidentally bumping into someone influential and embarrassing themselves. The Anonymity, while initially freeing, comes to wear one down. If nobody knows you from Adam or Eve, it might become difficult to know what you believe. Acquaintances can at least remind you who you are or who you used to be, and without that feedback, it grows difficult to remember who you are or were in this world.

Anonymity reliably produces ghosts. When banished, the Exiled still retained much of their former identity. After, that self starts to evaporate off. The confidence and self-assurance that might have always accompanied them before get shown the door and a hesitance might hinder each step. The Exiled seek cues for what they should do in social situations, for they're unable to conspire with friends to figure out how they might engage. They consequently become socially awkward beings and often seemingly thoughtless, too, for they frequently have no clue what's considered appropriate to do in a wide variety of novel situations. The rules for comportment vary widely between the various regions of this country, and these rules are rarely, if ever, published anywhere. They tend to be common knowledge among the locals and utterly unknown to every visitor.

Going to a supermarket tends to be a traumatic experience for anyone visiting from a distant region. The stores in the South hold widely different conventions than those in the North. Comportment depends upon the neighborhood in the Washington DC region, which straddles North and South. Slipping into a store across town can prove to be a shocking experience. I never grew comfortable with even the neighborhood markets in my own neighborhood there. I watched the locals and pantomimed as best I could. I'm sure my performances were unconvincing, and I showed ten thousand little tells that I was an alien, but what choice did I have? I needed to go about my activities of daily living even though I was suddenly living on Mars or Venus, depending; I couldn't always tell which. I began collecting curious affects, watching for clues and cues. This introvert even adopted the habit of talking to others while shopping, and once I noticed it, it seemed to be a shared experience between the locals. I found those excursions more enjoyable once I grew comfortable communicating with others. In my homeland, we tended to shop like wax figures, never mentioning shit to anyone but our immediate companions. In DC, shoppers seemed comfortable striking up conversations with anyone about absolutely anything while shopping. Only the carpetbaggers wouldn't engage, and I didn't want to appear to be one of those.

I used my newly found Anonymity in a thousand little ways. As I became more comfortable living without my protective skin, I began exploiting its benefits. I could easily claim ignorance when caught violating some rule, for I truly was clueless. I found that most would forgive my trespasses, perhaps because they'd been Exiled once themselves. I came to become comfortable even asking for directions when I inevitably got lost. My vulnerability became a better superpower than my Anonymity ever was, for with vulnerability came a disarming authenticity. I was never entirely powerless to influence, however impotent I at first felt. I came to understand that my former identity had protected but also blinded me to many possibilities, namely all those things a person like me would never engage in. Once Anonymity freed me from some of the more rigid elements of my identity, I found myself growing, stretching out into areas I'd previously assiduously avoided. I like to think I became a better man after I lost that significant part of my former identity. I might still be catching up to who I've become, but I sense myself a better man for that spate of Anonymity being Exiled brought.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved